(Editor’s note: This article was written in April 2008 and first published on the University of Cincinnati website. Lissa wrote the article for a research project that included indexing the magazine’s content and posting online the cover images for all issues.)

By Lissa Kramer

Jon Hughes looked away from the magazine and bent over in his chair, allowing himself to be consumed, for a moment, by a fit of laughter. When he had recovered, he removed his glasses to wipe his eyes and said, “That has to be a joke.”

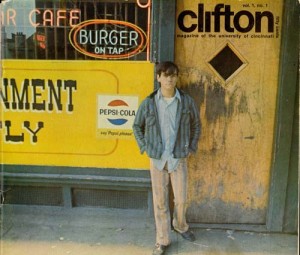

Jon had just finished reading a “letter to the editor” from the autumn 1973 issue of Clifton Magazine, the award-winning UC student magazine that ran from 1972 to 1994. The magazine took its name from the neighborhood in which the University of Cincinnati was located. The letter, written to Cliff Radel, was from a Baptist virgin who begged him to not “print any more four-letter words or dirty pictures because (she) might, just might, find (herself) enjoying them.” There are some in the Journalism Department today, including Hughes, who knew Radel and suspect that the whole thing was orchestrated by him.

Radel set the tone for future issues of Clifton Magazine when he promised in his first editorial to take “a sideways look at the University.” There was a lot going on in Clifton in 1972, and the student journalists made it a point to be in the middle of it. “Being the magazine of the University of Cincinnati entails certain obligations,” Radel says. Clifton appeared during a time when female students on state campuses were locked in their dorms at night. Coverage of the Kent State University shootings in 1970 during protests against the Vietnam War captured the spirit of campus demonstrations all across the country.

Lissa in 2008 researched the history of the University of Cincinnati student publication Clifton Magazine.

“All these people had rebelled from the News Record (the student newspaper at UC) and its staid presentations. We were a very motley crew,” Radel says. “Everybody was on fire. Nobody had to be told ‘Hey, you need to do some work.’ Being given the encouragement by Jon, and tacitly by the university, to do whatever the heck you wanted to; to be creative, to make a statement, to strive for excellence, especially in a city like Cincinnati, is one heck of a thing, and it’s an incredible opportunity.”

In the context of that era, the race riots of the late 1960s left the youth of the city, of all races, ready to fight. Cincinnati’s inner-city neighborhoods had a reputation for being unsafe, and Clifton was no exception. Many wandered into the serene surroundings of Burnet Woods, only to be mugged or worse (“Cincinnati Night Run,” Autumn 1972).

At the time, Ludlow Avenue in Clifton was not the thriving business and entertainment district that it is now. The Esquire Theater was closed and in disrepair. Graffiti covered many buildings. Up the hill near campus, McMillan Street was run down, and Calhoun Street was considered unsafe. Short Vine held amusing possibilities for students looking for a good time in head shops, boutiques, and bars – much like it does now – but it was a haven more for rednecks than hippies. At the time, hippies generally found peace and love in the neighborhood of Mt. Adams.

The films “Deliverance” and Woody Allen’s “Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex” were playing around town, and when the university ran the controversial erotic film “Last Tango in Paris,” starring Marlon Brando, police were sent to close the place down but couldn’t get in without a student I.D. Neither the projectionist nor Clifton Magazine backed down, and a review of “Tango” appeared in the next issue (“Marlon Brando and the New Film Hero,” Winter, 1972/73).

The magazine was in touch with the city. Clifton foretold of the organizational problems at concert venues in a story about Riverfront Coliseum (“Through Trial and Error: Crowd Control at the Coliseum,” Winter 1977/78). A year later, eleven people lost their lives at the coliseum during the Who concert on December 3, 1979.

The irreverent style of Clifton, according to the magazine’s first editor, Lew Moores, was influenced by Esquire, Rolling Stone, and Village Voice. At the time the “New Journalism” popularized by writers like Tom Wolfe was narrative nonfiction. Moores quoted a piece written by Wolfe in the December 1972 issue of Esquire that says “You’ve got to ask the questions of your subject that you have no right to expect answers to.” The style was practiced by the editors in stories about Union Terminal, student suicide and the incompetence of student government (“Union Terminal: End of the Line,” Autumn 1972; “IWISHIWEREDEAD,” Spring 1973; and “UC vs. Fingerman,” Autumn 1972). “The sideways look, I think I kept that up. I don’t need to see the who, what, when, where, why, I don’t need to see all that in the first sentence. There are too many people who do that. Nobody says, now wait a minute, let’s take a look.”

“A magazine will take on the personality of its editor,” says Hughes. Radel, who now works as an editor at the Cincinnati Enquirer, contributed pieces that were uniquely Cincinnatian. His love for Cincinnati is reflected in pieces such as “…The End of the Line,” an interview with the lonely dispatchers at Union Terminal who bemoaned the emptiness and silence of the place following its ending of passenger train service in 1972. “It was sad when I stood in the connecting corridor and gazed at the empty rotunda…I turned and looked down the darkened concourse whose 36,000 square feet of waiting room space was once jammed with travelers. Throughout the emptiness the omnipresent murals stared back at me, almost in disbelief and remorse. After talking with (the workers) I knew that over the years they had fallen in love with the place and I guess I had too.”

Clifton’s signature interviews share a common thread from the early 1970s through the mid-90s. The editors never shied away from high profile subjects like Andy Warhol (“Paul Warhola: Marking His Mark,” Winter 1989/90) or Jerry Springer, the city’s mayor and councilman before he became a television celebrity. Springer was once found out to have paid a local prostitute with a check (“Jerry Springer, the Cincinnati Kid,” Winter, 1974/75). On another occasion, Moores and William Ruehlmann sought an interview with Matt Koehl, the head of the American Nazi Party for a feature in the autumn of 1973, when Radel was the editor.

Regarding the art of interviewing, Radel says, “When I was a music critic I interviewed George Harrison and I was the only one talking to him, the only guy talking with him for twenty minutes, and I’m very shy. I had questions for him, so you talk to him. Or, if you want to talk to the American Nazi guy, you give him a call, and the next thing you know, he’s sitting in the room with you.” (Jackboots and Boats: An Interview with Matt Koehl,” Autumn 1973).

Wolfe’s narrative nonfiction technique was certainly lived up to when Moores wrote the story “IWISHIWEREDEAD” about UC student Wayne True, who jumped a few days after his birthday from the roof of Calhoun Hall in 1973. The story avoided the sensationalism one might expect from such a tragedy, but it was not lost on him that after maintenance staff had finished hosing brain matter from the pavement “students, with whom our future is invested …lit on the area like a pack of lame jackals, dragging their feet through the grass, looking and occasionally pointing.”

It is for articles like this and the generally innovative journalism that Clifton was chosen “Best All-Around Student Magazine” in the country by the Society of Professional Journalists in 1978 and 1979. The contributions of UC students and faculty were a feather in Clifton’s cap, not only for brilliant photography, but for graphic design and illustrations as well.

The response to Clifton’s style wasn’t always positive, however. Polk Laffoon, a columnist for The Cincinnati Enquirer, wrote in a 1974 article, “Clifton Looks at Cincinnati,” noted with some sarcasm, “…how seriously these kids take themselves.” Cliff Radel’s response to this quote is: “Why not take ourselves seriously? We may have been confident, because we were doing a good job, but we were not arrogant.” Serious students, though, can be irreverent jokesters, and Clifton provided a forum for their views. The substantial, thought-provoking stories were often found within a page or two of a bogus interview such as “A Candid Conversation with the Bashful Billionaire,” (August 1972), or a plea for the best porn story. There were also “office elves” and a “guardian angel” listed on the masthead.

Lew Moores once remarked, “I’m not so much interested in what will sell as what should sell if it were marketed correctly.” This view was taken by Moores’ successors as well, and in the magazine’s run of 23 years, it often conflicted with soliciting advertising dollars. Cliff Radel’s complaint about the difficulty of finding good literature and reading matter in “Bookstore Blues” criticized Lance’s Bookstore, located on Calhoun Avenue just south of campus. It is a lament still heard today as serious readers debate the quality of bookstores. The management of Lance’s took offense, however, and removed its ad from the magazine, reducing Clifton’s revenue.

Another example of this kind of fearless journalism practiced in Clifton was the article “His Kiss is the Beginning” (Spring 1973) a commentary about the lack of a gay scene in Cincinnati by a homosexual who struggled with coming out. A story like this may be somewhat ordinary today, but it was considerably controversial in ’73 and certainly would not have helped to fetch advertising dollars.

As Clifton’s advisor, Jon Hughes had to go to bat for the magazine a few times. The bookstore issue was one thing. Another issue was a discussion about the cover. He had to “persuade” the editors that they couldn’t put a picture of a man dressed like a priest with a nude woman on his lap on the cover (Winter, 1972/73). “I didn’t want to go to jail” he recalls. But those issues were only discussed occasionally. The last time his ‘guardian angel’ services were tested, however, he lost. When advertising revenue continued to sink in the mid-1970s, Hughes appealed to UC president Warren Bennis for budget assistance, but he declined. By 1993, the finances had been in a precarious state for two decades, and the lack of revenue became critical. After 24 years, Clifton finally lost this battle and the last issue, printed on grainy newsprint, came out in May 1994. That ‘letter to the editor’ was not a joke, remembers Radel. “We didn’t have to make up letters to the editor.” Through 70 issues the magazine kept up with the changing cultural landscape ot its readers’ lifestyles, their world views, and their adopted neighborhood – Clifton.

Selected Sources

The Cincinnati Enquirer

“UC’s Clifton Magazine Takes Regional Award,” April 12, 1976.

The Cincinnati Post

“Clifton Looks at Cincinnati,” January 1, 1974.

“Clifton Wins Award,” October 12, 1978.

“Making Ends Meet at Clifton,” April 14, 1980.

“Big 10 for Clifton,” January 30, 1982.

Hughes, Jon. Interview, April 3, 2008.

Moores, Lew. Interview, April 8, 2008.

Radel, Cliff. Interview, May 1, 2008.